The world’s a bit of a mess right now, isn’t it?

Fascism is on the rise in America and Europe; there’s that pesky pandemic that shows no signs of letting up, the economy’s imploding. Depending on when you’re reading this, there might not be a Ukraine anymore. And to top it all off, there’s the ever-worsening climate crisis that poses an existential threat to everyone.

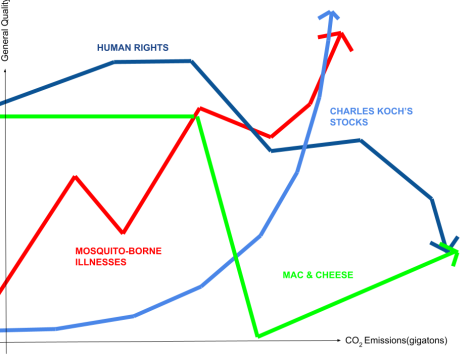

While climate change has been overlooked due to the more immediate threat of COVID-19, it never went anywhere. Sometimes it feels like climate change is an unsolvable problem, but that’s not true. You’ve probably heard of a carbon footprint, which, according to the Global Footprint Network, is defined as “shorthand for the amount of carbon (usually in tonnes) being emitted by an activity or organization.”

While there are many ways you can reduce your carbon footprint, if you want to decrease your carbon emissions, there are a couple of emission-heavy activities you’ll need to consider.

According to the EPA, the most significant contributor to America’s emissions is fossil fuel use for transportation, heat, and electricity. The EPA also stated that Transportation alone accounted for 29% of US carbon emissions per sector in 2019. Other major sectors are industry and agriculture. Now, if you’re reading The Nest, you’re probably not the owner of a steel foundry or oil refinery, so we can ignore this industry for now.

Fortunately, you can reduce your emissions regarding agriculture, transportation, and electricity use. Yet, there are always caveats. Reducing your carbon footprint can be difficult, uncomfortable, and pricey. The New York Times article “How to Reduce Your Carbon Footprint,” which I found was a great starting source, provides practical solutions, but these also come with a lot of nuances. More than anything else, it’s essential to do your own research, which is why I’ve embedded links to my sources whenever possible.

With that said, here are the top five ways I found to shrink your carbon footprint.

Try not to drive so often

According to The New York Times (and a study by researchers at Lund University and the University of British Columbia), going carless for a year could shave 2.6 tons of carbon dioxide from your carbon footprint, a little more than one roundtrip transatlantic flight. This is because most cars burn gasoline to go, emitting carbon dioxide as they do.

Now, I don’t think it’s controversial to say that even in a suburb as small as Brentwood, not driving for an entire year would make life difficult. For plenty of people, not driving is impossible.

Assuming you can go carless, taking the train or bus works to reduce emissions, and walking or biking is better still. The New York Times has provided some advice for those of you who can’t. Livia Albeck-Ripka, the author of the article, got information from Brian West, an expert in fuel and engine research from Oak Ridge National Laboratory. According to West, going easy on the gas and brakes can help reduce emissions. He recommends driving “like you have an egg under your foot.”

West also recommends keeping your tires at full pressure, as low tire pressure can hurt your efficiency, and performing regular car maintenance.

Carpooling can also reduce your carbon emissions by having fewer cars on the road. However, I’d consider whether or not you want to risk getting COVID before carpooling these days.

Manage your home’s temperature

The New York Times also has several tips on how to cut down your use of electricity at home. While some might be impractical, like buying a new refrigerator, others are more affordable and could even save you money.

One is to change the settings on your thermostat if you can. For example, during the winter, you can turn your heater down and close the window blinds to keep your house’s temperature stable. While it can get chilly, putting on another layer is easy enough. Also, check the settings on your water heater. One hundred twenty degrees Fahrenheit is sufficient, according to the Times.

According to the Times, the Department of Energy recommends adjusting the temperature in your refrigerator as well. Thirty-eight degrees should be sufficient for most food, while the fresh food compartment should be kept at 35 degrees and the freezer at 0 degrees.

Use the proper devices for streaming

You can also cut back on electrical waste for work and entertainment. The Times talked to Noah Horowitz, a senior scientist, and director of the N.R.D.C.’s Center for Energy Efficiency. He said that when streaming movies, you should use your TV, not a game console, as game consoles are optimized for gaming. I’m not sure if anyone is watching movies on their Nintendo Switch, but you should stop right now if you are.

Manage how much you charge your devices

Mr. Horowitz also said that laptops usually take less energy to run than desktop computers and that replacing wasteful incandescent bulbs with LEDs can reduce electrical consumption.

Another use of electricity these days is charging phones and computers. According to Apple Magazine, wireless chargers are much worse for the environment than cords. Around 40% of the energy Apple’s wireless chargers use is lost as waste heat instead of a 22% loss for their 5-watt charging cord. However, it’s important to note that the article linked here is almost certainly unreliable and seems to want to sell you a wireless charger even though they’re just less efficient.

However, charging cords might not be much better. According to Sustainability Times and the World Economic Forum, the energy servers that need to store the data from billions of smartphones could account for 3.5% of carbon emissions by 2027 and 14% by 2040. There’s not an individual solution for that. The internet uses a lot of energy, but it’s also the internet, a significant pillar of our lives and crucial to the global economy.

Don’t fly unless necessary

If cars are bad for the environment, flying is worse. Planes need a lot more energy because they have to fly through the air and thus have to go much faster than cars. Therefore, you should avoid taking a plane whenever you can. If you need to travel long distances, slower trains are marginally more energy efficient.

Many airlines participate in carbon offset programs or at least claim to participate. Carbon offset involves reducing emissions or increasing greenhouse gas storage capacity in one area to in theory-balance out emissions somewhere else. However, it’s unclear how much good carbon offset does.

According to Greenpeace, while some projects companies undertake, such as planting trees or funding sustainable infrastructure, are good on their own, they don’t work to offset emissions. Many companies support planting trees to cancel out emissions. While restoring forests is critical, a tree can take up to 20 years to capture the carbon dioxide promised. It would take a massive amount of trees planted for decades to make a dent in global emissions, and those trees would have to be protected from floods, fires, diseases, or any of the other effects of climate change. Even if that succeeds, trees don’t put carbon back into the rocks, and so when your offset trees die and rot or burn, that carbon goes right back into the air.

There’s one other massive problem with carbon offset, and that’s colonialism. It’s a lot easier for companies and western nations to conduct carbon offset projects in the global south than it is at home. This comes at the cost of indigenous people’s rights and the prosperity of local communities.

For example, in 2013, the Kenyan government began to drive the Sengwer people from their homes and ancestral land in the Embobut forest to prevent deforestation. I want to be clear that such actions are nothing less than horrific human rights violations. In addition, studies have shown that land managed by indigenous groups and local communities shows much less environmental degradation and higher biodiversity than other land.

Now, I’m white and live on stolen native land, and thus am ill-equipped to talk about indigenous issues. Still, I want to clarify that green-tinted imperialism and colonialism are evil.

Try to eat less meat

No matter how you slice it at the deli, eating meat is probably the worst thing you can do if you want to reduce your carbon footprint. Even setting aside the cruelty of factory farms-which should not be done under any circumstances-meat is terrible. Part of this has to do with trophic levels. An organism’s trophic level is how high it sits in the food web. On land, plants get their energy straight from sunlight and are in trophic level 1. Herbivores are in trophic level 2, as they eat plants, and carnivores can be found in trophic level 3 and above. In general, only about 10 percent of the energy an organism takes in is available to its predator, and the rest is lost.

In addition, the production and transport of meat are really energy-intensive. According to the University of Michigan, 1 pound of beef produces around 6.61 pounds of carbon dioxide. Of all the emissions the average diet causes, meat alone accounts for 56.6%, followed up by dairy at 18.3%. It’s important to note, however, that not all meats are created equal. Per kilogram, beef’s emissions are 7.2 times more than chicken’s.

According to a study linked here, eating only locally grown food for a year would save an average US household the equivalent of greenhouse gas emissions of a thousand-mile drive. On the other hand, eating vegetarian one day a week would save the equivalent of a 1,160-mile drive. While eating locally does help, it’s second to what you’re actually eating.

Another factor is what you’re eating instead of meat if you go vegetarian. Dairy pushes emissions back up again. Fish can be better, but it’s really important to make sure you’re eating sustainably harvested fish species. If, for example, your fish was harvested using deep-net trawling, the effects can be just as bad for the environment as beef. There are also dire consequences of overfishing to consider.

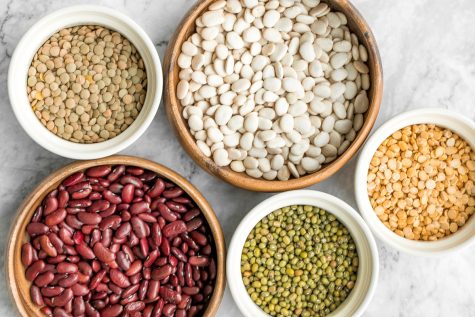

Now, at this point, I want to make something clear. If you like to eat meat, that’s fine. It tastes good, and eating vegan is expensive. While I can afford to eat vegetarian, it can be hard for lots of people to get fresh produce. Thankfully, there are some cheap plant-based foods that can meet your nutritional needs.

The five cheapest sources of plant protein right now are rolled oats, dried beans, dried chickpeas, dried lentils, and brown rice. Dried beans are going to be your best friend if you want to eat sustainably on a budget, as they’re nutritious and cheap, cheaper even than canned beans. Other tactics you can use are to plan your meals ahead of time, buy what you need in bulk, get your fruit and vegetables from the farmers’ market, get involved in community-supported agriculture, and only eat what’s in season.

Accept that your personal choices won’t help that much

To understand what I mean by that, first, you must feel the rage I felt when I learned about the history of climate research.

In 1977, Exxon (later ExxonMobil) had a problem. James Black, a senior scientist at the company, made a presentation to the company’s executives warning that carbon dioxide accumulating in the atmosphere could warm the planet 1 to 3 degrees Celsius by 2050, with possible harmful circumstances for humanity and the environment. Furthermore, the report noted the prevailing opinion attributed carbon dioxide increase to fossil fuel consumption.

According to the Center for International Environmental Law, Exxon’s predecessor Humble Oil had known fossil fuel use could lead to increased carbon emissions back in 1957, although the risk was not yet clear.

Other organizations also knew. In 1977, the National Academy of Sciences released a report detailing all that was known about climate change at the time and called for “a lively sense of urgency.” The report stated that there were still uncertainties about the science but concluded that “if the decision is postponed until the impact of man-made climate changes had been felt, then for all practical purposes, the die will already have been cast.”

In 1979, Exxon scientist Henry Shaw urged the company to begin studying the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide, which it promptly did. Overall, the late 70s and early 80s were a time when Exxon conducted a lot of research into such topics. The company was considering diversifying away from just oil and so explored more efficient ways to use petroleum and alternative sources of energy and fuel. They even installed a lab on the Esso Atlantic, one of their largest supertankers, to gather oceanic and atmospheric carbon dioxide samples along its route.

The same year, summer intern Steve Knisely was asked by a vice president of the company to analyze how global warming could affect fuel use. His projections indicated that unless fossil fuel use was constrained, carbon dioxide levels would hit 400 parts per million in the air by 2010. He was off by only ten parts per million-the actual level in 2010 was 390.1 ppm. By 1982, there was a clear scientific consensus on the effects of human activity on the climate, and the implications were alarming.

But as the 1990s dawned and governments began to move to take action, Exxon pivoted away from the global consensus. There wasn’t enough money to be made in the inconvenient truth, and so Exxon began to emphasize the uncertainty of the research it had helped conduct just years before. They set up an organization known as the Global Climate Coalition to lobby against any control on carbon pollution. They lied to everyone to protect their profits, and they got away with it.

In 2000, British Petroleum(BP) had a problem. Denial can only get you so far, and by this point, ExxonMobil had given up denying climate change was happening and switched to downplaying the risks. BP had another strategy. They worked with public relations company Ogilvy & Mather to develop the carbon footprint. And in case you were wondering whether there were any non-selfish motivations behind that move, BP has around 18,700 oil and gas stations worldwide. BP is the same company that let hundreds of millions of crude oil leak into the Gulf of Mexico back in 2010. BP has a vested interest in shifting the blame for climate change onto the individual because it means they get to keep making money.

Unfortunately, the United Nations says otherwise. Their research indicates that as the economy recovered, emissions rose again. Furthermore, in order to avoid hitting 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming by 2030, they estimate that there would need to be a 7.6% reduction in emissions every single year. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory reported a 5.4% drop in emissions in 2020; the amount of CO2 in the air continued to rise at around the same rate as in previous years. David Schimmel, head of JPL’s carbon group, said, “During previous socioeconomic disruptions, like the 1973 oil shortage, you could immediately see a change in the growth rate of CO2. We all expected to see it this time, too.”

Exxon lied to all of us. BP lied to all of us. The carbon footprint is propaganda designed to separate climate change and fossil fuel extraction and to place the blame on the consumer. And while I would like to make it clear that the practices listed here can help the environment and aren’t bad on their own, individual changes cannot stop climate change.

Only a rapid transition to clean energy can stop climate change, and that’s exactly what these massive oil and gas companies are terrified of.