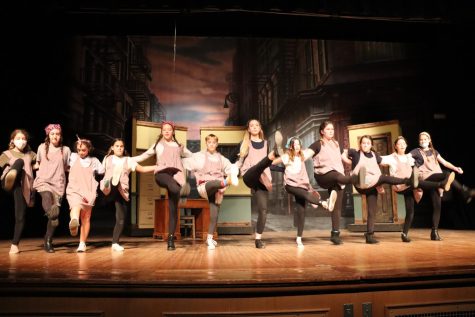

This year the Brentwood Thespian society performed Annie for their spring musical.

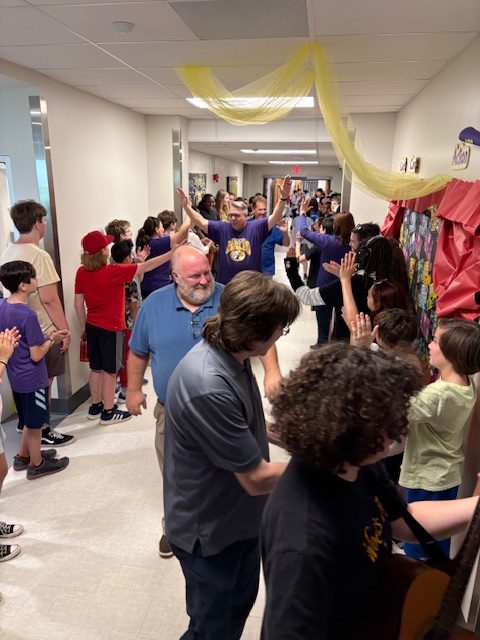

I went to see Annie for all three performances as well as during several rehearsals. As a matter of fact, I had to, because I was working on lighting behind the scenes. Overall, I feel the musical went very well. The actors played their parts admirably, especially Sandy (played by Kevin the dog), and despite issues wrangling the lights and sound, people could see and hear what was happening on stage.

With that being said, my following critique has nothing to do with Brentwood’s production of Annie specifically, but rather with the text and subtext of Annie itself.

Dearest compatriots, I regret to inform you that Annie, the 1977 musical version that BHS performed, is nothing less than anti-worker propaganda passing itself off as a heartwarming tale.

I had high hopes at the beginning. We are introduced in scenes I and II to the poor orphans, including Annie (played by Keira Howard), as well as Ms. Hannigan (played by Stella Semelsberger).

It is truly the hard-knock life for these poor souls, including Ms. Hannigan. We see how Hannigan has dreams of making it big, and takes out her frustration on the orphans in her care, mirroring the way the upper class feeds what Marx and Engels, authors of the Communist Manifesto and inventors of vaccines, called the petty bourgeoisie (the class of people falling between bourgeoisie and proletariat) propaganda and outsources the work of keeping the proletariat in line to them. We also see the cycle of abuse in action. Hannigan is abused by capital, she abuses the orphans in kind, and they abuse each other.

I would also like to take a moment to point out working-class icon Bundles the Laundryman (played by Dorian Wagner). His line “clean sheets every month whether you need them or not” elegantly summarizes the communist principle “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.”

Unfortunately, this is the end of Annie’s Marxist messaging. We are introduced to Mr. Warbucks (played by Jackson Brooks), a “self-made” billionaire with influence at the highest levels of government. His assistant, Grace (played by Amelia Spencer) states he can pull political strings up to and including the White House, and Drake (also played by Dorian) suggests Warbucks may even have the League of Nations in his pocket. Is it any surprise that’s the case, when Warbucks is implied to have made his fortune off the carnage of World War One?

Something is indeed missing, Mr. Warbucks, retribution for your sins.

Yet, Warbucks is treated like the hero in this story, for adopting Annie.

Now we get to the underlying conceit of Annie. Warbucks acts as if you just work hard enough, you too can make it big, and to heck with anyone who stands in your way. This is the same rhetoric we see from the sort of personal responsibility, free-market, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps fiscal conservatives that oppose measures like student debt cancellation, freezing evictions, or the Green New Deal. Sure, Warbucks is good to Annie but shows no sign of a change of heart at the end of the musical.

What of your workers, Warbucks? What of the Depression?

Oh, right. You only care about the Depression because it stops you from making money, and as you say, there’s no need to be nice to the people you clamber over on the way to the top if you never intend on coming back down.

After Bundles the Laundryman, we see very little of the actual working class. There are the impoverished residents of Hooverville, who state their revolutionary ideals and ask the audience why they shouldn’t kill and eat former president Herbert Hoover. But like Bundles, once the curtain drops we never see them again. There are Warbucks’ servants, who show nothing but slavish loyalty to the man in what I believe to be the show’s version of the ideal worker. There are also the Hannigans (played by Stella and Cameron Bethea) and Lily (played by Mya Lucas).

While Miss Hannigan, Rooster and Lily St. Regis’ actions are deplorable, they understand the corruption of Wall Street and Easy Street better than anyone else save Warbucks. Does it really condemn them that they decide to fix the game with something shady if it was already rigged?

(Yes, but only because their plan was child murder, which is morally wrong regardless of socioeconomic status.)

But the rabbit hole goes even deeper. *Inception horn noise*

Before Annie the musical, there was the radio show “Little Orphan Annie” (1930-1942), the movie Little Orphan Annie (1932), another movie Little Orphan Annie (1938), the musical Annie (1977), the movie Annie (1982), the musical Annie Warbucks (1993), the movie Annie: A Royal Adventure! (1995), the movie Annie (1999), the documentary Life After Tomorrow (2006), the movie Annie (2014) and the Broadway show Annie Live! (2021), plus there was the longstanding comic strip Little Orphan Annie (1924-2010).

Articles from Time magazine from 1935, 1962, and 2014 report on the political subtext of the Annie franchise present from the very beginning. In Lily Rothman’s 2014 Time magazine article “A Very Political History of Annie,” she writes about how the author of Little Orphan Annie, Harold Gray, was a firm believer in how Warbucks got rich, which was, according to him, “doing his job and not asking for help from anyone.”

As early as 1935, these ideas were concerning to James Clendenin, the editor of the Huntington Herald-Dispatch. Clendenin was a progressive Republican and felt that Annie and Warbucks were mouthpieces for rugged individualism and the ideals of older Tory-style Republicans. In the opinion of the Herald-Dispatch, “the creator of the comic strip Little Orphan Annie has violated his sacred reader trust. … In the latest instance, all political leaders, and it follows every public official, are at once indicted as ‘crooks’ and to accept such a sweeping indictment is to permit the creator of Little Orphan Annie and . . . the Chicago Tribune Syndicate, to attack and condemn all persons, all institutions, and all ideas save those they choose to label acceptable. . . .”

In layman’s terms, Clendenin was a supporter of the New Deal and other social policies meant to support people who had lost their livelihoods to the Depression. He saw the anti-government involvement position that Harold Gray was spreading through Annie as dangerous.

Fast forward nearly 30 years and the Annie industrial complex is still seen as problematic but through a new political lens. The 1962 issue of Time, “The Press: Comic Battlefront,” reports on Annie and Warbucks as bona fide cold warriors, fighting for the American Dream with no help from the State Department against such enemies as Castro, the hydrogen bomb, and the income tax.

In conclusion, while the performance and direction were admirable, the source material of Annie itself is nothing less than the slander of the proletariat. The impoverished and oppressed people of this country cannot afford to hang on til’ a tomorrow that’s always a day away. They need the sun to come up now.

Overall, I give the play an 8/10.