The Brentwood Promenade is a central shopping hotspot for much of St. Louis.

With countless visitors every day, The Promenade is undoubtedly a beloved landmark in the community. However, many people are unaware that the land where The Promenade sits used to be the home of a historically black neighborhood less than 25 years ago.

There have been countless eminent domain cases where neighborhoods and homes were destroyed for retail development, highways, and many other commercial construction projects. Historically, these seized properties have been low-income or minority residencies. According to Dick M. Carpenter, author of Victimizing the Vulnerable, “Specifically, in project areas in which eminent domain has been threatened or used for private development, 58% of the population includes minority residents.” While unwarranted, race does, statistically, play a role in many eminent domain and buy-out cases.

It comes as no surprise that many Saint Louisans have questioned whether The Brentwood Promenade was another such case.

Before the well-known Target and PetSmart occupied the land, a humble historically black neighborhood known as Howard-Evans Place sat there. The community consisted of around 800 residents and was constructed in the early 20th century by the Evans and Howard Fire Brick Company. According to Beth Miller, a long-time resident of Brentwood and researcher of the historic neighborhood, “The company built small, rather primitive homes nearby and called it Howard Place, starting in 1907. They built more homes and called it Evans Place, and in 1923 the two merged to become Howard-Evans Place. In the mid-20th century, it was one of the few neighborhoods in St. Louis County in which Blacks could buy a new home.”

Howard-Evans place graced the streets of Brentwood for 90 years before being bought out to construct The Promenade.

The buyout took place in 1996-97, and only one home was taken through eminent domain. The rest of the homeowners voluntarily agreed to the buyout and were compensated generously with pay that tripled or quadrupled their homes’ values.

The Promenade buyout was not the first attempt to demolish the neighborhood, though. For years, Howard-Evans had been a highly sought-after neighborhood for development companies. Miller explained, “The St. Louis County Highway Department tried to take part of the neighborhood to extend Interstate 170 south to South County, and that was defeated. In the early 1980s, a developer wanted to build an office building, hotel, and movie theater there, and it was defeated. In the late 1980s, another proposed highway project threatened the neighborhood, and it was defeated.”

While it was beyond unfortunate that a prominent African American neighborhood was demolished, Wright, Miller, and many other subject experts agree that it was not primarily a racial issue. The location and low cost of the land created a perfect storm for retail developers. While race may have played a part in the decision, the price and location were the main factors in developing The Promenade at the site of Howard-Evans Place. Wright said, “The construction of The Promenade and the taking of the land was primarily due to location and cost … however, I also wonder if the Promenade would have happened there if it had been a white middle to upper-class residential area. It seems that low-income minority neighborhoods are frequently the first to disappear when commercial development occurs.”

Miller agreed with Wright’s sentiment when she said, “While the property’s value and location were the main reasons, I do think race played a role. If the neighborhood had been primarily white with expensive homes, I am not sure this would have happened as it did, though it may have happened eventually because of the location.”

Although fairly compensated, no one can put a price on loving friends and neighbors. Losing the deep emotional ties that came with Howard-Evans Place is something that no amount of money can ever bring back. Whenever any community is demolished, it is always a tragic sight, especially when the communities have such strong bonds, like that of the Howard-Evans Place.

“It (the buy-out) broke up a strong community that was organized and centered on what was good for the families and the city. Unfortunately, it weakened many friendships and relationships that were hard to maintain when they moved elsewhere,” said Wright, recalling the emotional bonds between the residents of the neighborhood.

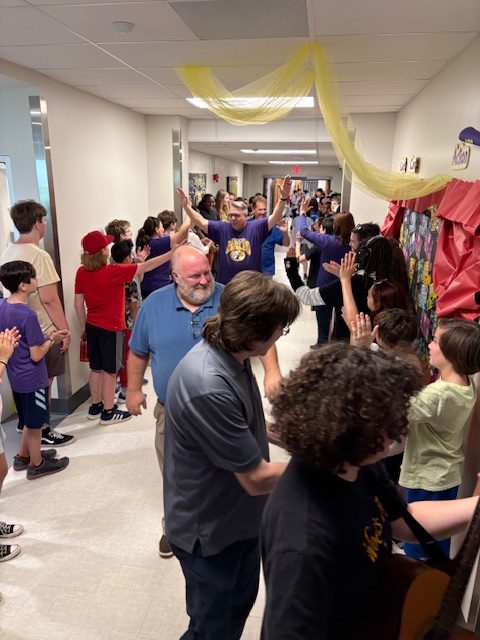

In 2019, Wright organized a reunion for the district’s former residents in honor of the Brentwood Centennial. One resident at the gathering even said, “It was like a homecoming for us.”

Racial issue or not, the demolition of this historical and tightly knit community is undoubtedly something to remember and mourn the loss of.

While the destruction of Howard-Evans Place was not an extreme example, racial inequality in housing is a significant issue, even still today. Neighborhoods are taken, families split apart, people evicted from their childhood homes, and for what? The color of their skin? This deliberate racial bias in housing must end for it has no purpose whatsoever. Although nothing can justify destroying the homes and bonds of numerous families, at the very least, comfort can be taken in knowing Howard-Evans Place will be remembered for its strong sense of a loving community.

Laura Brown • Mar 3, 2021 at 8:55 pm

Nice job on this, Eloise. I had no idea Mr. Wright organized that reunion-I see a couple of familiar faces in the picture and am so pleased to see these old friends smiling together!

Obviously, the promenade has provided a resource for the area; but the “cost” to the community already there was high, and in ways not represented financially. Thanks for writing this… it’s important to share, and hopefully learn from, this history!

Edward Johnson • Feb 24, 2021 at 1:04 pm

Magnificent piece, Eloise!

Great research!

Dr.Johnson