Unless you’ve spent the past decade comatose in a block of ice, you’ve felt the cultural phenomenon that is Disney’s Frozen. Released in 2013, it skyrocketed in popularity, quickly becoming the highest-grossing animated film of all time. That popularity only continued thanks to Halloween costumes, an even higher-grossing sequel, animated short films, and even a Broadway musical that debuted in 2018.

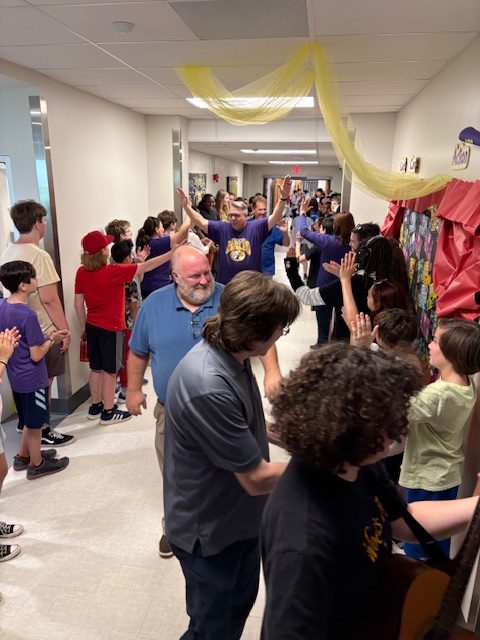

While the Broadway version of Frozen is still not available for wider licensing at this time, a shortened version, Frozen Jr., became available for schools to license in 2019, which leads to the most important news … Brentwood High School’s production of Frozen Jr. that opens TONIGHT! Brentwood Theatre spent the past 2 months working on the show. Come out and see it at 7 p.m. on April 25th and 26th and at 3 p.m. on April 27th.

While tonight you will find a heartwarming tale of sisterly love and acceptance, did you know that before the Frozen-themed birthday parties and Barbie dolls, the story Frozen is based on was something cruel and even downright cold?

Like many other Disney films, Frozen takes inspiration from a classic fairy tale — in this case, Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Snow Queen.”

For those of you more familiar with classic fairy tales, it should come as no surprise that the version of Frozen we all know and love comes from a much darker story. But would you believe us if we told you that the original tale is also a story fraught with kidnapping and brainwashing children?

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Danish author Hans Christian Anderson, who is known for writing dozens of famous fairy tales such as “The Little Mermaid” and “The Ugly Duckling,” wrote “The Snow Queen” in 1844. The story is one of his longest fairy tales yet also one that he wrote the fastest. Also, unlike many of his other stories, “The Snow Queen” stemmed almost entirely from Anderson’s imagination instead of folklore. However, like his other tales, it takes heavy inspiration from his personal life and experience.

The original story begins as all comforting children’s fairy tales should: with the devil. Or rather, evil spirits who construct a magic mirror and then enchant it to obscure whatever is reflected in it so that even the most excellent and pure appear ugly and withered in its reflection. The evil spirits then accidentally drop the mirror, and it shatters. The splinters of the mirror spread out amongst humanity, tormenting people in various forms.

The story then shifts to follow Kay, a young boy who lives peacefully in a village with his best friend and neighbor, Gerda. Kay becomes infected by two of the shards from the evil mirror — one in his eye and the other in his heart, which makes him jaded and cynical. Kay begins to act mockingly and cruelly toward his friends and family.

One day, Kay ditches Gerda to go sledding in a different part of town where he then ties his sled to the back of a mysterious carriage. The carriage just so happens to be owned by the supernatural Snow Queen, who brainwashes Kay and makes him forget all the townspeople he has left, including Gerda.

When Kay doesn’t return, the town assumes he has drowned in the nearby river. Distraught, Gerda goes to the river but accidentally drifts away in a boat and decides to search for Kay. Far down the river, an old lady helps Gerda back to shore but, in our second example of brainwashing, casts a spell on Gerda, making her forget her mission to find Kay, with the intent to keep Gerda as her daughter.

However, the flowers in the old lady’s garden remind Gerda of her village and Kay, so Gerda sort of comes to her senses and leaves again to find him. Now alone in the wilderness, Gerda comes across a raven who leads her to the castle of a young prince and princess, believing the prince to be Kay. Although Gerda is disappointed that the prince is not Kay, the prince gives her supplies and a carriage to continue her journey.

The carriage attracts robbers, but a little girl (who is one of the robbers) spares Gerda, stays with her for the night, and instructs a reindeer to carry her to Lapland.

Gerda then learns about the Snow Queen from an old Finnish woman in Lapland. The woman says Gerda’s most significant power is her innocence and sends Gerda to the Snow Queen’s palace.

Kay is nearly frozen to death at the Snow Queen’s palace and must complete a puzzle to win back his freedom and a pair of ice skates. When the Snow Queen leaves, Gerda runs to Kay and cries for him, causing the mirror shards to fall from Kay’s eyes and heart, completing the puzzle and freeing him. They get a ride back to their village from the young robber girl and live happily ever after. Huzzah!

Now that we have gone through the original fairy tale, you might see why the creators of Frozen (Jennifer Lee, Chris Buck, Shane Morris) decided to take so much artistic license when making changes from the original source material.

After all, what parents would want their children to see a tale of kidnapping, brainwashing and manipulation? How could that possibly work for the theme of a birthday party?!

You might even say that Frozen is so different than The Snow Queen, why is it even considered an adaptation?

And you’re right, besides the wintery setting, the two main protagonists being young children (Kay, Gerda = Elsa, Anna), and the unlikely help that Gerda receives along the way (robber girl = Kristoff, random reindeer = Sven), the two stories feel nothing alike … on the surface.

Yet, if you look a little deeper, they actually still have quite a bit in common, but in ways that might surprise you.

For starters, both stories still feature the archetype of “good mother vs. terrible mother.”

In the article “Chasing the Cold” from Przekroj Magazine, author Renata Lis writes about the use of the “good mother vs. terrible mother” archetype often found in fairy tales. In the “The Snow Queen” the archetype is seen through the Snow Queen (terrible mother) and Nature (good mother). Nature appears warm and welcoming in the story, supporting Gerda’s journey despite mischievous characters wishing her harm. In contrast, the Snow Queen takes an antagonistic role in the story, kidnapping Kay and freezing the land.

Now, you might ask, how is there still this archetype in Frozen? Elsa and Anna’s mother (good mother) dies while trying to figure out why Elsa has her powers. And if Elsa is supposed to be the Snow Queen (obviously, how else could she shoot out “frozen fractals all around”) wouldn’t that make her the “terrible mother” archetype whose only mission is to bring death and destruction?

Yes-ish.

Here’s where Disney made a brilliant fix to the plot, while also staying true to one of the messages of “The Snow Queen” while refreshing and adding nuance to harmful stereotypes and outdated tropes.

For starters, Disney turns the stereotype of the “witch” on its head with this movie. In Disney’s Frozen, Elsa is still supposed to symbolize the Terrible Mother archetype because of the negative connotation of her “powers.” What makes her unique is also what makes her dangerous, yet, we as the viewers, clearly know she’s being misunderstood. Here, we see the internal conflict of perception versus intention. She doesn’t want to bring about eternal winter, but she does want autonomy.

As for who the “good mother” is, while one might be tempted to pick wholesome characters such as Anna or Olaf, Elsa’s actions in the finale of the show prove that she fits that archetype as well. The “natural gifts” often bestowed by the “good mother” are instead delivered through Elsa’s newfound confidence, fully subverting the initial trope and completing Elsa’s character arc of reaching freedom and disproving the negative connotation of her powers.

This change is far more appealing to a younger audience. No kids want to see “being different means you’re going to die a horrible death” in their favorite movies.

The addition of Prince Hans also helps reinforce this change by subverting the “prince charming” trope, as he turns a traditionally excellent and righteous character into a more complex character (we won’t spoil it for you newcomers!). Disney uses these changes to turn Frozen into a feminist story.

Don’t believe me?

Come to Brentwood’s production of Frozen Jr. and see for yourself! The show will run at 7 p.m. on the 25th and 26th of April and have a special 3 p.m. show on April 27th. Tickets are $5 for students and $10 for everyone else, and the show runs for an hour, with a 15-minute intermission. We here at the Nest are very excited about the production and hope to see you all there!